By completing the following steps, they are more likely to avoid bad money: Investors have enhanced their focus on organizations with demonstrated health outcomes improvements, high and sustained consumer engagement with low churn, ability to withstand economic downturns, and additional quantitative measures that enhance their likelihood of betting on a good egg.įounders should be equally diligent in ensuring they pursue good money.

#Venture capitalist healthcare how to#

How to avoid giving and receiving bad moneyĪs venture funding slowed in H2 2022 and is continuing to do so into 2023, founders and investors alike must be more diligent about whom they seek funding from, and to whom it is granted. This is what founders-and funders-want to avoid in order to create value through venture investments in health care. Funders put pressure on founders to grow quickly, scale their solutions, and prove they can attract more consumers to their service offering or platform. Bad money is unfortunately what we have seen the most of in VC-backed digital health entities in recent years. The opposite of good money is “bad money.” This type of funding is impatient for growth but patient for profit. Good money is funding that is patient for growth but impatient for profit in an organization’s early days. Leaders can avoid this focus on growth in their early days by taking only “good money” from funders. Scaling an unprofitable venture simply scales a money-losing machine. Proving desirability and profitability, not proving the ability to grow, is the first critical step of a successful venture. In an organization’s early days, it must iterate its business model to prove that it has a viable way to make money and can be sustainably profitable. If growth is the primary objective, a potentially disruptive idea will fail by these standards before it has an opportunity to prove its value. By definition, disruptive markets are small as they start to get off the ground. The reason many ideas get shaped into sustaining innovations, and thus forced on a “march towards failure” is because funders require these potentially disruptive ideas to grow quickly.

As Clay Christensen outlined in The Innovator’s Solution, “Because the process of securing funding forces many potentially disruptive ideas to get shaped as sustaining innovations that target large and obvious markets, the very process of getting the money to start a venture actually sends many of them on a march towards failure.” But whether that funding is made of good money, or bad, will make or break their trajectory. “There is good money, and there is bad money.”įor startups to get off the ground, they need funding. Let’s dive into why that is and what leaders can do about it. Good Money Bad Money Theory lends some insights into why we’ve seen the rapid growth and quick demise of many entities in the VC-backed health care arena in recent years. But, what we can do is use proven theory to explain what we are seeing. We can’t apply the specific reasons why one organization failed or succeeded to all organizations receiving the same type of funding.

But others, like Omada Health and Maven Clinic provide success stories.

Yes, certain venture capital investments have led to value destruction, lost lives, and decreased health and well-being. As it relates to this last question, I’ll argue that venture capital is not “bad” for health care as a whole. Instead they are different shades of gray.

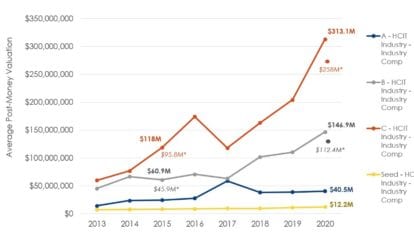

And many have concluded the answer is “yes.”īut the answers to questions as complex as this are rarely black or white. The negative outcomes have led some to ask, “Is venture capital just bad for health care?”. Who, or what is to blame for these negative business outcomes, and more importantly, for the lost lives and negative health impact? The question at hand is why does this happen? As the influx of venture capital (VC) dollars flowed-and have since slowed-into digital health startups, we’ve seen many companies soar to great heights, only to meet their demise months later.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)